The AI Supply Chain Tug of War

Big Tech is absorbing demand risk from the AI supply chain. How long can it last?

Here’s the question now being asked all across the AI ecosystem: Is there a way for someone else to take on the demand risk from AI, while I capture the profits?

Today, Big Tech companies have stepped up to alleviate some of this tension. They are acting as risk-absorbers within the system, taking on as much demand risk as they possibly can, and driving the supply chain toward greater and greater CapEx escalation.

In part one of this piece, we’ll walk through the tug of war between supply chain players over risk and profit. In part two, we’ll unpack the instability of today’s equilibrium.

Who Should Bear the Demand Risk from AI? Who Should Capture the Profits?

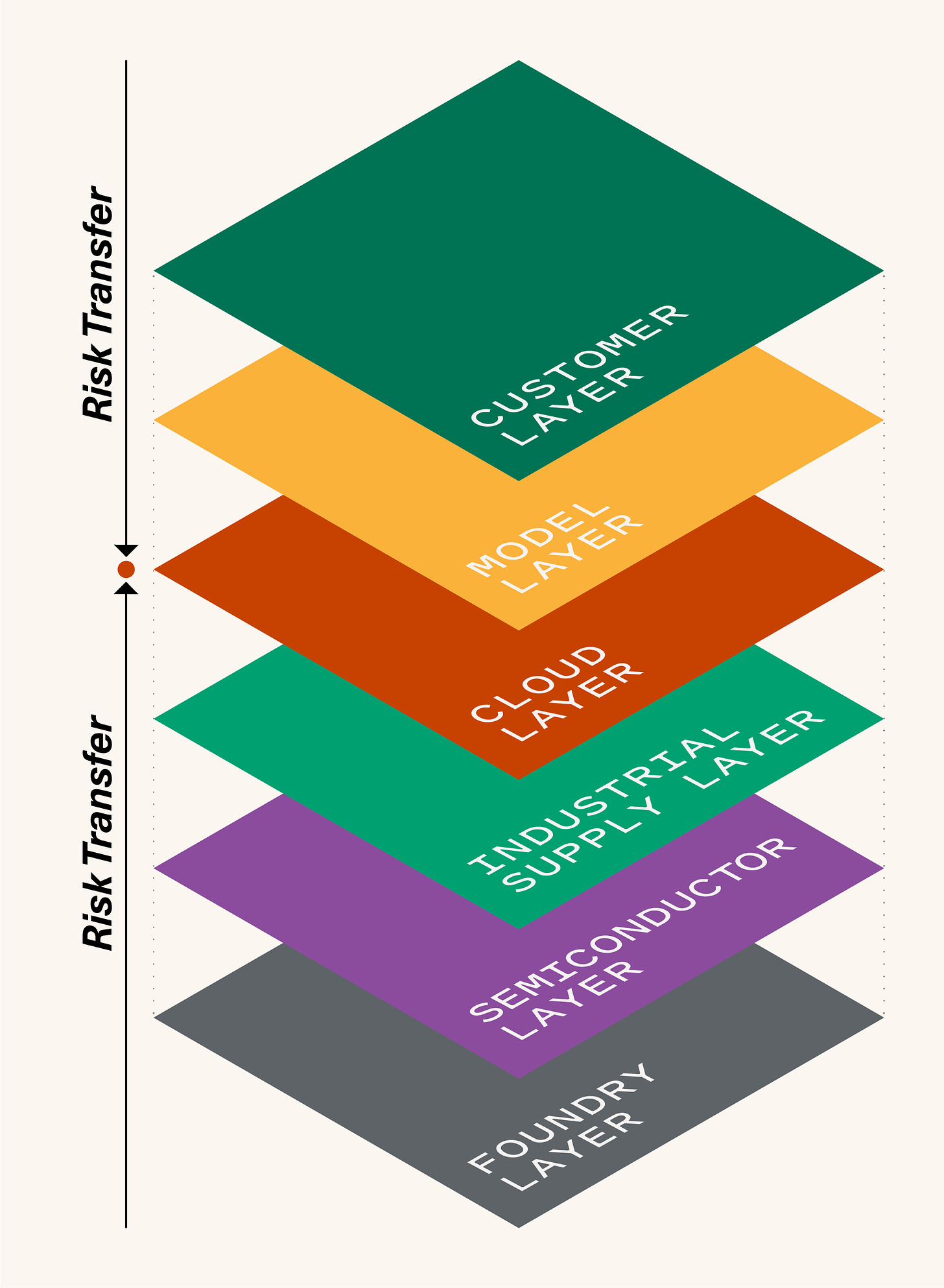

In the supply chain, risks are transferred from suppliers, who need to build CapEx to manufacture products, upstream up to their customers, who pay a margin that compensates for this capital expenditure over time.

Each player wants to maximize profit while minimizing risk. This creates supply chain conflict, which lurks behind the scenes, and exposes itself in pairwise game theoretic interactions between suppliers and their customers. Below, we’ll give one example of how this tension manifests for each layer of the supply chain.

Foundry Layer: TSMC is Nvidia’s manufacturing partner. The more manufacturing capacity TSMC builds for Nvidia, the more it is exposed to future demand fluctuations. The fewer fabs it builds, however, the more problems Nvidia will have with its supply shortage. Thus arises the core tension in this relationship: TSMC’s incentive is to have just enough availability to serve Nvidia, and nothing more. Nvidia’s incentive is for TSMC to build as much CapEx as possible, to maximize availability. In this relationship, TSMC has all the leverage—it is the dominant pure play foundry globally and serves many customers, including Nvidia’s competitors. Thus, as we try to forecast the future of AI, we should expect the stable equilibrium to be that TSMC underbuilds capacity relative to peak demand. An example where this will manifest: TSMC is currently planning out future CapEx for its 2nm node. We might expect that however much capacity TSMC chooses to build, it will be less than the amount that Nvidia and other AI chip companies will have requested.

Semiconductor Layer: One of the great ironies of AI is that while the big cloud companies and Nvidia are all members of the “Magnificent 7”—and their fates tend to be correlated as investors wax and wane on AI’s potential—these companies are actually diametrically opposed on many dimensions. For example, the cloud companies are extremely resistant to Nvidia’s profit capture in AI, and they are all working on their own competitive chips. At the same time, Nvidia has been trying to compete with its biggest customers by directing chip supply to new entrants like Coreweave and by building its own cloud business with DGX cloud. The semiconductor tug of war is primarily about profit margins.

Industrial Supply Layer: The industrial supply chain is another realm where we can see the ripples of risk transfer at work. When we talk to Big Tech companies, one consistent refrain we hear is that they are trying to buy out all the manufacturing capacity they can get for industrial components like diesel generators and cooling systems, and also for commodities like steel and electrical transformers. Their suppliers find these orders volumes almost hard to believe and are actually resistant to serving this demand; they are concerned that if they double their manufacturing capacity, they will be left with excess capacity in the future. To resolve this conflict, the cloud companies are making big commitments—promising to buy many years of supply ahead of time—to incentivize industrial CapEx.

Cloud Layer: The cloud layer is the lynchpin holding everything together. We will discuss this in depth in part two of this post.

Model Layer: If you are OpenAI, Anthropic or Gemini, you want to get as much compute as possible for your frontier model, because more compute means a more intelligent model. If you are Azure, AWS or GCP, however, you want to direct GPU or CPU compute to Enterprise customers—this is your main business. Thus, the main conflict at the model layer is over data center capacity allocation. Since the model layer today is not profitable, these allocations are negotiated between cloud executives and research lab leaders. These negotiations are made more complicated by ownership structures, where the research labs are either partially or wholly owned by the clouds. As model sizes grow by 10x, these power struggles will only be exacerbated.

Customer Layer: Hooray for the customer! At the end of this long and complex chain, there is an application layer AI startup or an Enterprise buyer calling an API and querying a foundation model. What is “demand risk” to everyone else is “the luxury of choice” to the customer. Customers can use AI models on-demand, and they can easily switch between vendors at their discretion. If customers ever decide the AI is not useful enough, they can turn it off. The entire supply chain is in service of this customer, who benefits from competition and supply chain efficiency.

The entire supply chain hinges on the last link—the customer. The supply chain is to some degree positive sum: Everyone benefits as the total profit dollars in AI increases. However, as the prior examples highlight, it can also be zero sum: My revenue is your cost, in the case of Nvidia and the clouds. My CapEx is my risk and your benefit, in the case of TSMC and Nvidia.

The tug of war dynamic also helps to explain some of the supply shortages we continue to see in AI, such as shortages in the industrial supply chain. No matter how much pressure they get, there’s only so much demand risk suppliers are willing to take on.

A Fragile Equilibrium: Big Tech is Propping up the Supply Chain

Today, the big cloud giants are acting as risk-absorbers in this system. They absorb risk from their downstream partners Nvidia and TSMC through large orders that generate huge short-term profits for these companies. They also absorb risk from upstream partners: The cloud companies are the largest source of funding for frontier model companies and they subsidize end customers in the form of low API prices and bundled credits.

Here are four concrete examples of this risk-absorption mechanism at work:

GPUs—Now or Later? It’s in Nvidia’s best interest to sell as many H100 GPUs as possible now, and then sell more B100s and next-gen chips in the future. It’s in hyperscalers best interest to fill their data centers with GPUs on as-needed basis (this means building data center “shells” and then only installing GPUs once demand materializes). What is actually happening in the market? Hyperscalers seem to be competing with one another for GPU supply and placing big orders with Nvidia to make sure they don’t fall behind. Rather than waiting, they are stockpiling GPUs now and paying twice: First, a hefty upfront expense, and second, higher expected future depreciation.

Data Center Construction: The real estate developers who build and assemble data centers are getting a pretty sweet deal. These companies take on almost no demand risk. Developers like CyrusOne, QTS, and Vantage build data centers for big tech companies, but they will only start construction after they’ve signed a 15 or 20-year lease. And they structure these deals so that they can pay back their investment during the lease period alone—they limit their “residual risk” around the long-term value of the data center asset (e.g., even if prices collapse after the lease period, they can still make money). The long-term demand risk squarely sits with the cloud providers.

Off Balance Sheet Arrangements: We’ve all seen headlines of late about GPU financing deals and the debt that’s being issued to finance GPU purchases. What many people don’t realize is that most of this debt is actually backed up by rental guarantees from Big Tech. These agreements seem so robust that many debt investors see themselves as investing in Big Tech corporate debt, not in GPUs. The incentive for Big Tech in these deals is to turn an upfront capital expense into a recurring operating expense. This is a very clear example of how Big Tech companies—even when they are not directly doing the financing—are actually backstopping much of the investment activity happening in AI today.

Research Lab Funding and Exits: The Big Tech companies are the largest source of funding today for AI research labs. The biggest labs—OpenAI and Anthropic—are each backed by one of the large clouds. The recent exits of Inflection, Adept and Character demonstrate that it may be increasingly difficult to operate without such a backstop.

Conclusion

Supply chain players understand AI’s $600B question, and they are working to navigate it—maximizing their profit margins and minimizing their demand risk. The result is a dynamic tug of war between some of the most sophisticated companies in the world.

Today, the tug of war has resulted in a temporary equilibrium. Supply chain players are offloading their demand risk to Big Tech, to the maximum degree possible. Big Tech companies—either due to AI optimism or oligopolistic competition—are stepping in to absorb this risk and keep CapEx cranking.

This equilibrium is fragile: If at any point the tech giants blink, demand all along the supply chain will decline precipitously. Further, the longer the Big Tech companies continue to double down on CapEx, the more they are at risk of finding themselves deeply in the hole should AI progress encounter any stumbles.